When Performing Medicine’s virtual class ‘Drawing in the Anatomical Zoom Room’ caught SWW DTP PhD researcher Sarah Scaife’s eye, she applied to the DTP2 Placement and Skills Development Fund to cover the cost of joining in.

Performing Medicine is a respected and innovative organisation bringing performance research and techniques to the medical sector. As they put it, “Our work provides opportunities for health professionals, artists and members of the public to share in a dialogue about the benefits that the arts can bring to health and education.” My supervisor Dr Bryan Brown introduced me to their work when Suzy Willson, its creator, gave a guest presentation in the University of Exeter Department of Drama.

My doctoral research explores the concept of medicines of uncertainty. As an artist-scholar, this practice-based research leans into Medical Arts & Humanities, which is new to me as a field of academic study.

Lived experience of cancer treatment means that my usual encounters with health professionals are as a patient, rather than an influencer. As a scholar, I seek ‘engagement, influence and impact’ . To move between these positions with fluency, I need to learn more about medical agendas and where these overlap with the potential of embodied artistic practice-as-research.

Read on to see how the vexed history of wax anatomical models stirred up my enquiry.

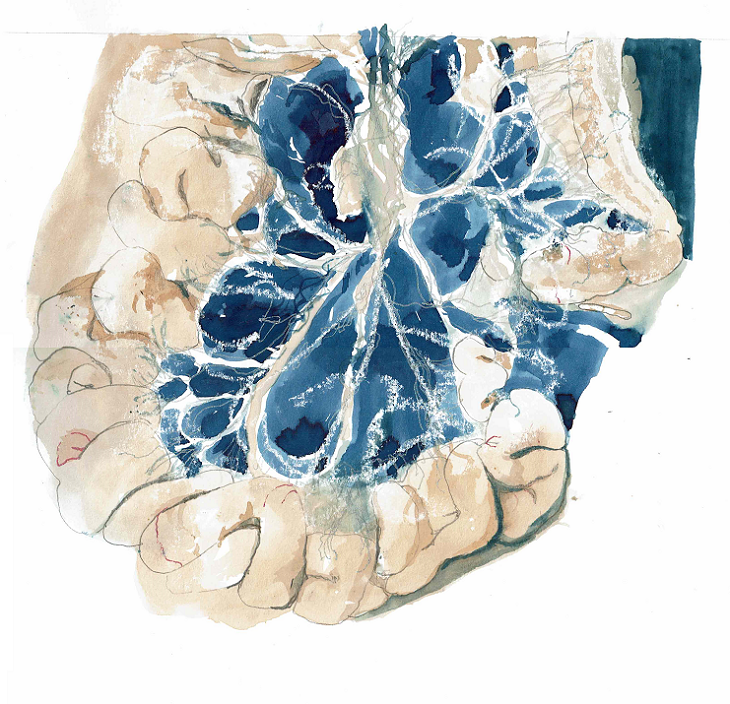

Sarah Scaife 2021, digital scan of wax-resist and ink drawing in A3 sketch book (intestines)

Drawing in the Anatomical Zoom Room

‘Drawing in the Anatomical Zoom Room’ was enthusiastically and expertly delivered by Eleanor Crook. She describes herself as “a British sculptor with a special interest in mortality, anatomy and pathology who exhibits internationally in fine art and medical & science museum contexts.”

The class brought together a dozen artists, therapeutic body workers and medics. This was a unique opportunity to meet others in a hybrid creative/medical environment, a space to learn, contribute and refine our strengths. The group included people I would not normally meet on equal footing. My recent contact with the medical and therapeutic world centres on ongoing lived experience of post-cancer treatment management, often lying on my back, half-dressed and being touched.

Wax objects recast through non-verbal thinking

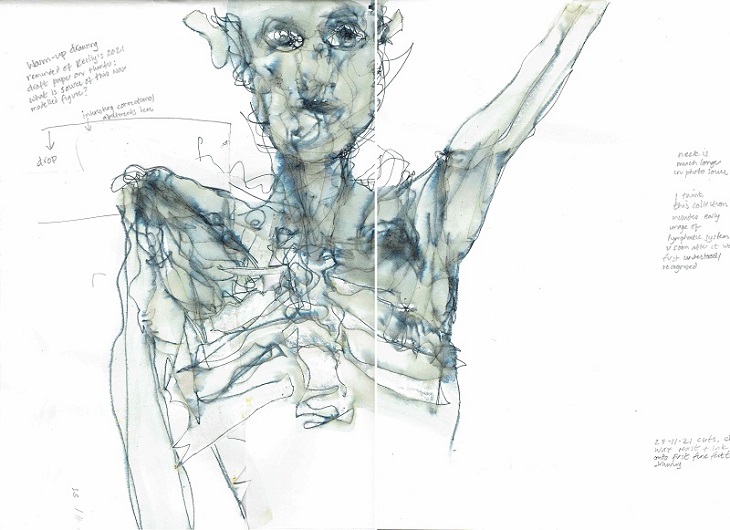

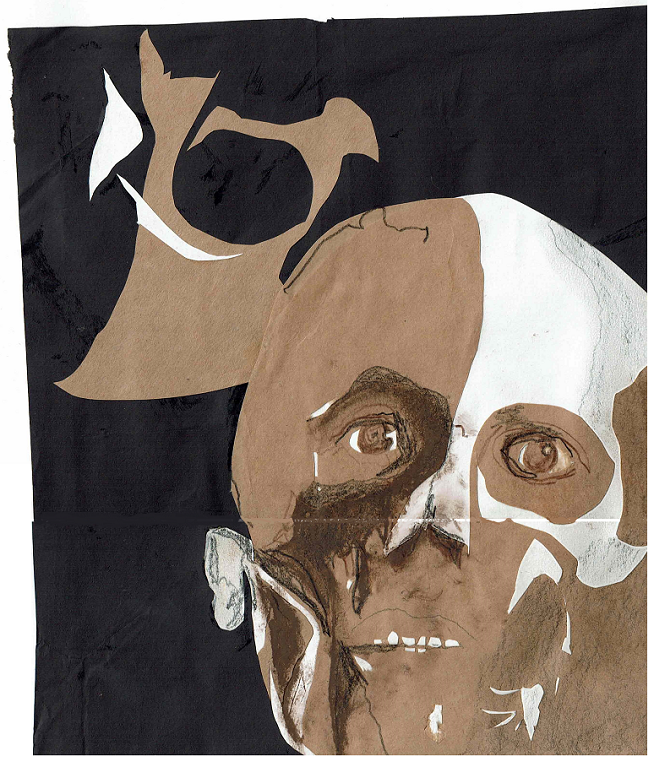

Over four evenings, Eleanor’s gripping presentations on wax anatomical collections modelled in the 18th and 19th century, ranged provocatively across science, technique, treatment, the European Enlightenment and – rather more often than I had anticipated – my own revulsion. In the second half of each session, whilst responding to this content by making new anatomical artwork from images of the historic wax models, we chatted.

Over the course each participant developed several experimental drawings of the wax anatomy models in the museum collections presented. Drawing on my creative expertise, I could engage with my colleagues as an intellectual peer rather than as a patient. The course offered a stimulating blend of specialist input, conversation, listening and non-verbal thinking.

It feels important to say that there were times in these classes when I found both the conversation and the Western historical discourse around anatomical research rather disturbing. Making offered a means to work with this discomfort; turning it into a material investigation through research drawing offered a productive means of enquiry. Edwards identifies this skill as “using visual, non-verbal cognition to process perceptions.”

Embodied resonances

The more-than-human underpins my research and I’m particularly interested in the animacy inherent in materials. It is my view that artistic practice-as-research, like healing, lies on the oscillating boundary between the material and the immaterial.

Despite the uneasiness, I became intrigued by Eleanor’s discussion of wax, a surprisingly enduring material originally created within the bodies of living beings. As a former member of staff at Wakefield Art Gallery, I knew Henry Moore’s (1940-41) wax-resist drawings of frightened people sheltering in the London Underground during the Blitz. Referencing these, I made drawings of the partially dissected human bodies recast in wax.

Sarah Scaife 2021, digital scan of wax-resist and ink drawing in A3 sketchbook (dissection)

There were embodied resonances to reflect on. One wax model we were invited to draw showed an uncomfortably raised arm without skin. It resonated with one of my own photographs, taken to actively document the experience of cancer treatment, here post-mastectomy radiotherapy.

Sarah Scaife 2017, photograph of self, taken in mirror

To feel into the dissection process by drawing directly with a knife, I created a cut and collaged image of a wax model’s skull reminiscent of my own bald and underweight head during chemotherapy.

Sarah Scaife 2021, digital scan of knife cut collage with over drawing in A3 sketchbook (skull dissection)

Grisly underpinnings of anatomical research

‘Drawing in the Anatomical Zoom Room’ confirmed my grisly awareness about the underpinnings of anatomical art made in the name of scientific progress . The models and diagrams of an idealised anatomy are created from a composite of multiple human bodies. In 18th and 19th century Europe, these human bodies were routinely procured in the context of enforced marginalisation or even retribution. Thus, medical knowledge is abstracted from the bodies of those who gave no consent.

Renowned modeller, anatomist and academic at the University of Bologna, Anna Morandi Manzolini (1716-1774) was an unusual woman at the forefront of this research. Many have benefitted from her pioneering practice-research but, like much pioneering, it involved overlooking and looking away from as well as looking at. Today, artists are called on to look into some of the complex and difficult tensions embedded in historical and contemporary health systems, for example through the Confabulations programme.

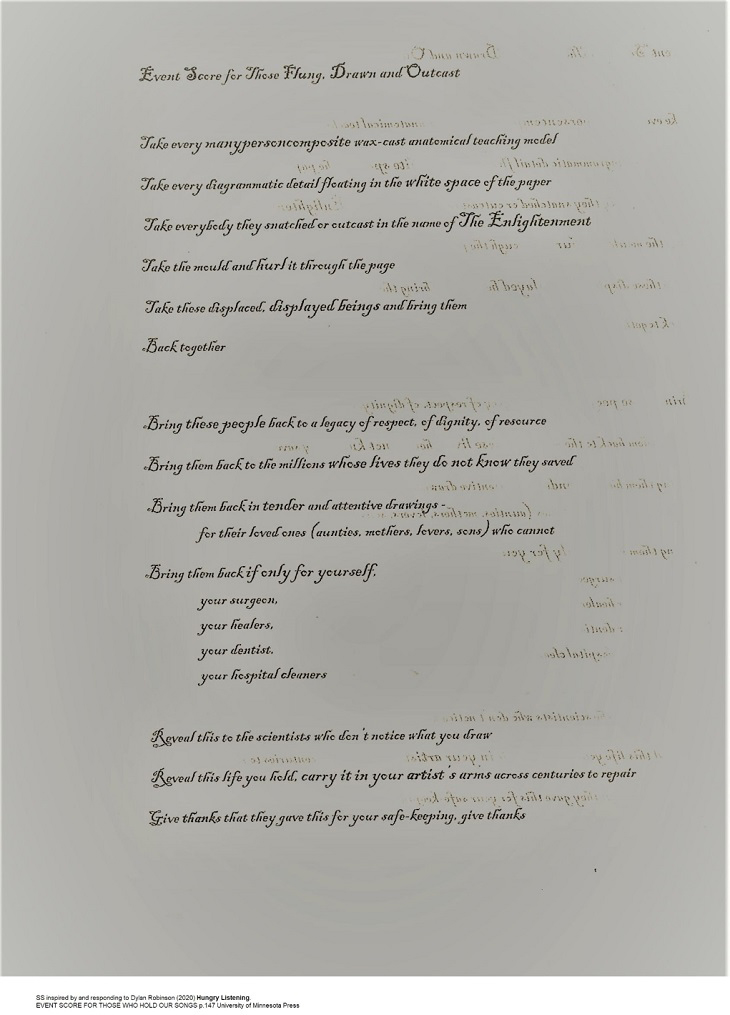

A deeply felt connection arose for me with the compelling contemporary writing of Indigenous scholar Dylan Robinson. My forebears come from rural poverty and displacement, not wealth or establishment. Inspired by Robinson’s EVENT SCORE FOR THOSE WHO HOLD OUR SONGS , I want to explore a relation to these marginalised people who had their bodies dissected so that generations later people like me could be treated.

To express this, I drew on the archaic technique of parody. In a pre-modern Western musical tradition, parody did not imply humour. Rather it was an honouring process for generating sacred musical texts, through creatively reworking an already existing and respected piece.

Imagined exchange

These notions are explored in a text work which might have come from an imagined conversation between Robinson, me and Morandi. It is set out as if from Morandi’s handwritten notebook.

Sarah Scaife 2021, If Anna Morandi, Dylan Robinson and I could meet. Digital Work. (Event score in the style of Anna Morandi’s C18th notebook, inspired by and responding to Dylan Robinson 2020 EVENT SCORE FOR THOSE WHO HOLD OUR SONGS)

I’d like to finish this post with a transcription of this imagined notebook page.

These people, with their bodies and personhood caught in the hierarchical binaries of scientific and economic progress, could have been my ancestors. Maybe they were yours too?

EVENT SCORE FOR THOSE FLUNG, DRAWN AND OUTCAST

Take every manypersoncomposite wax-cast anatomical teaching model

Take every diagrammatic detail floating in the white space of the paper

Take every body they snatched or outcast in the name of The Enlightenment

Take the mould and hurl it through the page

Take these displaced beings and put them

Back together

Bring those people back to a legacy of respect, of dignity, of resource

Bring them back to the millions whose lives they saved

Bring them back in tender and attentive drawings –

for their loved ones (aunties, mothers, lovers, sons) who cannot

Bring them back if only for yourself,

your surgeon,

your healers,

your dentist,

your hospital cleaners

Reveal this to the scientists who don’t notice what you draw

Reveal this life you hold, carry it in your artist’s arms across centuries to repair

Give thanks that they gave this for your safe keeping, give thanks

Biography

Sarah Scaife is an artist-scholar who tunes in to the overlaps between being-in-a-body, listening and mutual space. Her practice-based PhD enquiry explores Medicines of Uncertainty in a more-than-human world, asking how polyvocal performance methods might reveal novel ways to articulate and attend to spells of illness. Sarah is a first year SWW DTP2-funded doctoral student in the Department of Drama at the University of Exeter, co-supervised in the Department of English, University of Bristol. See more of her work at berry brown gown.

- Performing Medicine: Drawing in the Anatomical Zoom Room

- Performing Medicine courses

- Suzy Willson (2021), creator of the Performing Medicine programme; Professor of Movement, Arts & Medicine at Barts and The London School of Medicine & Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London. Presentation to the Department of Drama, University of Exeter, 04 June

- Vitae Researcher Development Framework (RDF) 2011 (PDF, 567kB)

- Eleanor Crook

- Edwards, Betty (2012) Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. London, Souvenir Press Ltd, 4th edition, p.40

- Henry Moore (1940-41) Shelter Drawings. Henry Moore Foundation online catalogue.

- Reilly, Kara (2021) work in progress presentation to the University of Exeter Magic & Esoterism Research Group, 27 October

- Confabulations: Art Practice, Art History, Critical Medical Humanities 2021-2023 is an on-line programme leading up to an edited volume of texts, artworks, and documentation of artworks, in association with the universities of Durham, Leicester (UK) and Queens (Canada).

- Robinson, Dylan (2020) Hungry Listening. University of Minnesota Press, p.147

Categorised in: Student Blogs