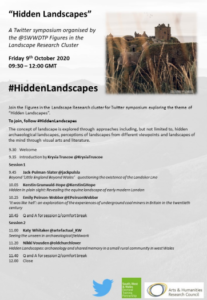

The event was originally planned for March 2020, as a one-day symposium consisting of a series of 20-minute presentations, but as the date coincided with the beginning of the first Covid-19 lockdown we were unable to go ahead. We therefore decided to have a virtual symposium instead. The presentations were divided into two sessions (each with time for questions at the end), and each presentation comprised a 20-tweet Twitter thread. Although the method of dissemination was new to some of the presenters, it was fairly straightforward, and a useful exercise in condensing information into short and engaging bursts of text. Using Twitter as a platform allowed us to interact with a much wider audience than would otherwise have been possible, who could either view the various presentations and join the Q&A sessions live, or revisit at their own convenience.

‘May we heartily recommend that you check out the Twitter papers shared today as part of @SWWDTP’s online conference: #HiddenLandscapes. A truly superb set of engaging and insightful threads!’. Landscape Survey Group

Krysia Truscoe introduced the symposium.

Krysia Truscoe introduced the symposium, pointing out that almost any landscape is a palimpsest not just in a physical way but also due to the layers of meaning inherent within it. The concept of hidden landscapes was explored by the presenters in various ways, including linguistic landscapes, physical landscapes hidden underground or lost from view, landscapes as seen through visual arts and literature, and perceptions of landscapes from different viewpoints and through shared memory.

Beyond Little England Beyond Wales: questioning the existence of the Landsker Line, Jack Pulman-Slater.

Jack Pulman-Slater (Cardiff University & University of Bristol)’s presentation, entitled Beyond Little England Beyond Wales: questioning the existence of the Landsker Line, explored the applicability of this invisible linguistic divide to modern day Pembrokeshire. Although the linguistic division of Pembrokeshire began after the Norman invasion of c.1070, Jack pointed out that the Landsker Line is a term first used in 1939 to denote the visible (e.g. in place-names and church architecture) and cultural division between widely English speaking southern Pembrokeshire (‘Little England Beyond Wales’) and Welsh speaking northern Pembrokeshire. Jack argued that focusing on the Landsker Line leads to an unhelpful emphasis on a superficial difference in linguistic landscapes rather than the people who live there, and that although there are genuine cultural and linguistic differences between northern and southern Pembrokeshire, a more nuanced reality is evident through a study of population data, census information, voting patterns and contemporary trends in education policy.

‘It was like hell’: an exploration of the experiences of underground coal miners in Britain in the twentieth century, Emily Peirson-Webber.

Emily Peirson-Webber (University of Reading) is researching the British mining industry through oral history and material culture. Her presentation, ‘It was like hell’: an exploration of the experiences of underground coal miners in Britain in the twentieth century discussed the physical and psychical landscape of the coalmine as experienced by her interviewees (former miners). She explained how the distinct underground culture of the pit was characterised by dark humour and an intense camaraderie; how the physical landscape literally entered miners’ bodies through dust inhalation, and how the darkness, heat and constant threat of injury and death became part of miners’ psyche. Pit closures in the late twentieth century severed miners’ physical ties with the pit and the redevelopment of colliery sites meant the loss of long-standing topographical markers. However, miners continued to be haunted by their experiences underground, and feel a strong emotional attachment to the hidden landscape below.

Hidden in plain sight: Revealing the equine landscape of early modern London, Kerstin Grunwald-Hope.

Kerstin Grunwald-Hope (Bath Spa University) explored how the equine encounters in antiquarian John Stow (1525–1605)’s Survey of London help the reader make sense of urbanisation and the Reformation. Her presentation Hidden in plain sight: Revealing the equine landscape of early modern London, focused on the changing equine landscape of Smithfield and Cheapside. With reference to the Agas map, Kerstin showed that Stow’s general statements and references to specific places highlight how London’s expanding population put pressure on the road network and water sources (e.g. the former Horse pool in Smithfield had by Stow’s time become ‘much decayed’ and was known simply as Smithfield Pond, and the urbanisation of Cheapside, where spectacles such as the Cheapside Tournament had formerly taken place). She then highlighted that his portrayal of an early modern lack of care for horses and disdain of the popular use of coaches (in contrast to an idealised past) show his unease at the prioritisation of the individual over the community and his nostalgia for the Catholic London of his youth.

Seeing the unseen in Archaeological Fieldwork, Katy Whitaker.

Katy Whitaker (University of Reading)’s presentation, Seeing the unseen in Archaeological Fieldwork, was a reflection on the difference between the idealised and real-world landscapes of undertaking research, focussing on the hidden landscapes of her research on sarsen stone and people’s relationship with it over the last 5000 years. She explained that because sarsen stone is located on and in superficial geological deposits (rather than being part of the bedrock) it is difficult to place in a particular landscape. Although there are some dispersed sarsen quarries, where stones lie closely grouped together and have been extracted, they are often difficult to access, necessitating different ways of engaging with the landscape (e.g.using historic aerial photographs to map the extractive features of a lost quarry in the Chiltern Hills and a stereoscope to trick the mind into seeing in 3D, then digitally drawing features in GIS). Where it was possible to visit and survey a sarsen quarry, Katy noted that the process of data-gathering, writing up and analysing the results, and drawing conclusions were all products of archaeological practice as opposed to how the quarry was experienced in the past by those who worked it.

Hidden Landscapes: archaeology and shared memory in a small rural community in west Wales, Nikki Vousden

The final presentation, by Nikki Vousden (universities of Exeter and Reading), was entitled Hidden Landscapes: archaeology and shared memory in a small rural community in west Wales. It focused on the community of Silian and its landscape, where hidden archaeology (represented by redundant buildings and their contents, and above and below-ground archaeological features) and shared community memory are in danger of being lost. Ephemeral landscape features include earthworks best seen after light snow, and a nearby antenna enclosure visible only as parch marks during drought conditions. Nikki explained how shared memories of more recent date are characterised by a strong sense of loss due to the removal of communal buildings from the social landscape, but how a new project to transform the redundant church into a community hub aims to reverse this and develop a strong community identity underpinned by the archaeology and social history.

The presentations were well received on Twitter, with many people engaging to ask questions, comment and retweet. We had some really positive feedback, including this from the Landscape Survey Group:

‘May we heartily recommend that you check out the Twitter papers shared today as part of @SWWDTP’s online conference: #HiddenLandscapes. A truly superb set of engaging and insightful threads!’.

Categorised in: Latest News